A ski-run, a community, a signature on the snow

Celebrating the first 40 years of the World Cup

The air up there is tense and vibrant. People hold their breath throughout the valley. The silence of the mountains, usually patient and gentle, is instead charged today with electricity. There is only the metallic sound of ski bindings closing, the sharp click of the edges of skis on the icy ground, the rustle of the wind in the trees, the crunch of boots on the hard snow and the deep, measured breaths of the athletes on the starting line. Up here, on the Gran Risa, every detail is amplified. The athletes’ gazes are fixed, sharply focused on the run. The anticipation becomes palpable. The crowd begins to gather, along the fences and in the stands at the end of the run. The chants gradually grow louder. Some spectators shout out the names of their favourites, others wave flags, yet others huddle in their down jackets with a hot cup in hand. It is a thrilling moment, full of anticipation and adrenaline. There is an exciting new chapter about to be written in the legendary history of the World Cup, right here and now.

A 40-year-old history

In December 1985, for the first time a small Ladin valley nestled between the pale peaks of the Dolomites appeared on the great stage of the Ski World Cup. At the time, few could have imagined that that debut—won by a certain Ingemar Stenmark—would mark the beginning of one of the most fascinating, enduring and significant stories in the world of skiing. Today, forty years later, Alta Badia is a fixed point and an unmissable date on the calendar.

“Over the years, this simple race has been transformed into a truly international event with an increasingly rich and involved backing” emphasizes Markus Waldner, Chief Race Director of the men's circuit, which has seen many different slopes and even more exciting races. “The logistical and economic demands of large temporary infrastructures have led to the introduction of a second race, in order to maximize the use of the entire facility. As such, alongside the giant slalom, we have added the slalom, the night parallel, and then the slalom again.” Today, the format includes the giant slalom on Sunday and the slalom on Monday.

The Gran Risa is therefore a “classic” that combines spectacle and technique, passion and precision in a tough, tree-shaded slope that takes your breath away from top to bottom. It is much loved and feared by athletes and because of all this, it boasts a podium reserved only for the best. But there's much more behind this icon: there is a story of intuition, vision, hard work and courage. Above all, there's an entire community that believed in an ambitious and visionary project which even today, 40 years later, provokes powerful and overwhelming emotions, both here in the valley and wherever great skiing enthusiasts gather together.

The person who imagined the impossible was Marcello Varallo, a former competitive alpine skier, downhill specialist, member of the Italian national team between the late 1960s and early 1970s (in 1972 he participated in the Sapporo Winter Olympics) and former president of the Tourist Association. When visiting international slopes and looking at the major Alpine stages, Varallo began to ask himself “Why not here too?” That dream, almost an obsession, soon became solid reality and something that Varallo still remembers with considerable emotion, while a smile betrays his pride in its origins. “That dream took shape in 1985 thanks to the collaboration with Hubert Dalponte and a project shared with Val Gardena: a Ladin Three Days event.” The first giant slalom on the Gran Risa was an instant success. The enthusiastic crowd, the impeccable organization and the incredibly tough slope beloved by coaches and athletes alike were elements that convinced even the most sceptical. From that moment on, the World Cup would never be without Alta Badia.

The secret to success, then and now? Vision and solidity. “From the very first year” says Varallo “the expenses were covered entirely thanks to the support of the institutions, Dolomiti Superski, and sponsors”. There were no unnecessary risks, no biting off more than anyone could chew. “If you start off with debts, you won't get far” he states bluntly. Yet what he remembers most fondly is something else entirely. “Already, there were 500 of us for that first edition, all volunteers, all united. Without that community spirit, we would never have made it”. It is precisely this sense of belonging and of deeply-rooted cooperation that still makes the event so special today.

The legend of the Gran Risa

Anyone who lives in La Villa in Alta Badia feels it, sees it and lives it. It's there, always, above everything and everyone. The Gran Risa isn't just a ski run, it's a part of the collective identity. From every window, every street, every house in the village, it’s there, looking at you, imposing, familiar, almost maternal. Its name in Ladin means “opening in the forest,” a slope that descends directly from the summit of the plateau to the valley, a clear line that cuts through the forest like a ray of light. In summer, it was the route used the loggers, who slid fir and larch tree trunks down it. In winter, it became the setting for the most sophisticated spectacle in the World Cup. A white two-lane track: on one side, the skiers descending; on the other, the eyes chasing it towards the horizon. When, every December the World Cup returns to Alta Badia, the valley comes to a halt, people breathe in as one, and the tension is like a bow string, because for forty years on that slope, a shared identity has been created, and every edition, every curve and every finish line is a new page written in the snow.

What makes it unique, for expert eyes and feet, are above all its technical characteristics: gradients of up to 69%, leg-breaking walls, blind turns, changes in pace, and snow worked until it becomes “hard as marble.”

Yet behind this perfection, the delight of top-class skiers, lies a magnificent feat of engineering and human skill. For over forty years Sergio Tiezza, a longtime engineer and member of the Board of Directors has been in charge of the transformation of the run. “I have always been involved in the technical aspects” he says. “Every modification, every detail, every gate and pole was and is the result of meticulous study.” It was he who introduced the famous Giat humps, for example, today one of the most iconic sections of the Gran Risa. However he also oversaw the complex technical developments required by the FIS, especially in terms of surface preparation. “In the beginning, the run just had to be white” he explains “while today, a density of 800 kg per cubic metre is required, which effectively is ice. Skiers have become power athletes, and the slopes have to tolerate enormous loads.” And the Gran Risa, of course, can't be any different. Only perfection is allowed.

Preparation, therefore, requires days and nights of continuous work, with teams of technicians, snowcats, and snow cannons that work non-stop. Weather conditions are often unstable, but the goal remains the same: to offer a flawless slope, down to the last centimetre in order to combine spectacle and safety. And when Nature rebels, the answer — once again — is unity. During one edition marred by bad weather for example, even the Army stepped in to save the race with the Tridentina Alpine Brigade. “I remember the scene as if it were yesterday” says Marcello Varallo. “Trucks full of Alpine troops were already there at dawn, ready, in uniform, with jackets, gloves and all the gear. They beat the snow by hand, literally pounding it for hours.” It's during moments like these that you understand the real power of this event: an entire valley moving in unison. “If you want to go it alone” concludes Varallo “then don't even start, because you've already lost before you’ve begun.”

And so in forty years, a competition has only had to be cancelled once. It was a disappointment for that year, certainly, but if you look at it in perspective, it is still a remarkable and almost unique achievement.

A ski run for champions

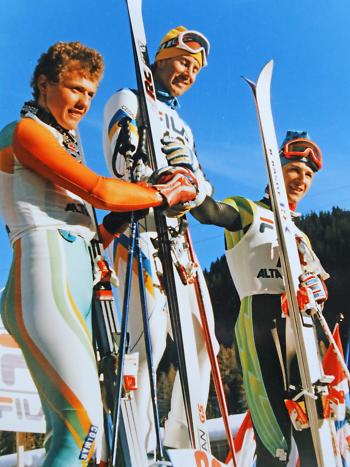

On the Gran Risa, every victory is another seal on the legend. It's not a race like any other: it's a test of maturity, a rite of passage. Here, you don't win by chance. Here, you make history. The great names of the past know this well, those who have carved their names on the hard ice of the slope. It consecrates those who dare. Alberto Tomba's four unforgettable victories, Marcel Hirscher's six giant slalom victories, one parallel slalom victory, and one slalom victory—elegant, surgical, unstoppable—and finally, Max Blardone's three. Then there are Ted Ligety's three victories, with his rounded, perfect skiing, not to mention Hermann Maier, Bode Miller, Aksel Lund Svindal, Alexis Pinturault and Marco Odermatt: each with their own style, each tested by an unforgiving run, each capable of having left a mark, a gesture, a fragment of glory.

But perhaps no one has set the hearts of the crowd on fire like Alberto Tomba. Brazen, powerful, magnetic: four times on the top step. It's said that sometimes he even skipped the preview run: he knew the Gran Risa like the back of his hand. 1991 was unforgettable. He started strong, tore through a gate and the cloth wrapped around his face. Yet he didn't stop, he hammered blindly on, as if every curve was written in his body. He crossed the finish line first and the roar of 40,000 people erupted under the Alta Badia sky. A legend.

But the magic of the Gran Risa isn't just about gold medals and podiums. After dominating the race in 2012, Marcel Hirscher donated the entire prize money—over €18,000—to the local population which had been hit by a landslide. A silent, powerful gesture, and more eloquent than a thousand words.

Finally, the Gran Risa is also home, as Roberto Erlacher, the only athlete from Alta Badia to reach the podium, knows very well. It was 1985, the first edition of the World Cup. Erlacher finished third, behind Stenmark. “As a child, I used to sneak under the fences to watch the training” he recalls with considerable feeling “and then, years later, I was there, on the same podium. A dream come true.” In 1986, Italy took everything: Pramotton first, Tomba second, Tötsch third. “I finished sixth” Erlacher smiles “but it was the dawn of a new era for Italian skiing.” And he tells a forgotten story: in 1982 in Alta Badia, what many consider the first Super-G in history was held, even though the discipline had not yet been officially sanctioned. “There were no FIS points, no defined order, with a new course and 180 starters, and I started with bib number 180. It's one of those things that few people remember but it's a piece of history, and it happened here.”

A competition already written into the future

Today, the heritage of the original vision that inspired the courageous racers in 1985 is in the hands of Marcello Varallo’s son Andy, president of Dolomiti Superski and the Organizing Committee. Under his leadership, the World Cup continues to be a driving force for tourism, social and cultural development in Alta Badia.

“Thanks to the event's television coverage, tourist arrivals in the valley increased by 250% between 1985 and 1988” explains Varallo. “But the real stroke of genius was the scheduling of the race before Christmas, which brought forward the start of the ski season, and even today allows us to convey an image of reliability, even in years with little natural snow”.

There is also the fact that “major investments with a view to the future have been made in a latest-generation snowmaking system. This is capable of producing snow in less than 48 hours, thus making the most of the few cold windows available in November” emphasizes Markus Waldner. This is a crucial choice in ensuring dependability and continuity for an event strategically positioned before Christmas which, especially in this 40th anniversary edition, will be a tremendous celebration, a real “ski festival” with significant international attendees, enhanced infrastructure in the stands, and the promise of a show worthy of its legendary history.

However, the event's most important value, according to Varallo, remains human. “During the World Cup, hoteliers, hut guardians, students and ski instructors work side by side. It's a moment in which the valley recognizes itself as a community.” This event generates more than just economic value. “No event is 100% sustainable, but today sustainability also comes from social cohesion, collective responsibility and a sense of civic duty.”

Perhaps this is the secret behind forty years of success: a region that has believed in itself, transforming passion into organization and organization into tradition. It is somewhere in which the mountains unite, where each edition of the World Cup is the result of a silent yet powerful collective effort that can clearly be felt, from the dare-devil curves of the Gran Risa to the hearts of every enthusiast eagerly waiting for the next champion.

Anna Quinz is the creative director and co-founder of the franzLAB communication studio and publishing house, along with franzmagazine.com, a contemporary Alpine culture magazine. She has been involved in territorial marketing and publishing for many years with a particular focus on the re-narration of mountains and Alpine tourism.